Learn out about shear walls and how they play a critical role in the structural stability of buildings.

Introduction

Shear walls play a critical role in the structural stability of buildings by providing stronger resistance to lateral loads. As trends in construction shifted towards high-rises and tall buildings in general, they have become even more important.

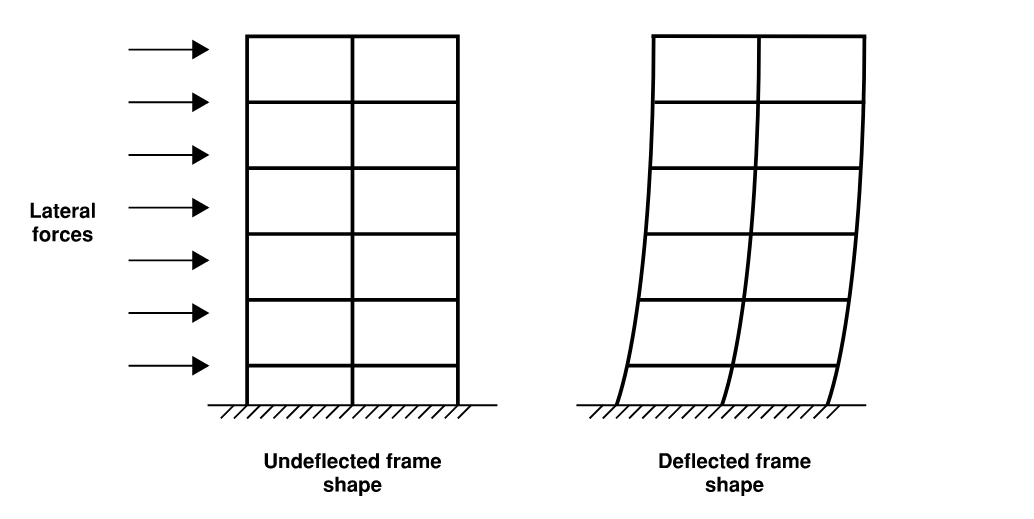

Lateral loads, such as wind and seismic forces, cause structures to sway and deflect (as shown in Figure 1). Without proper bracing and resistance against these loads, the structure's occupants may experience discomfort, or in the worst case, the structure may fail completely. One of the ways to limit the lateral sway and deflection is to increase the size of beams and columns - however, this method is costly and increases dimensions, which may not be permitted.

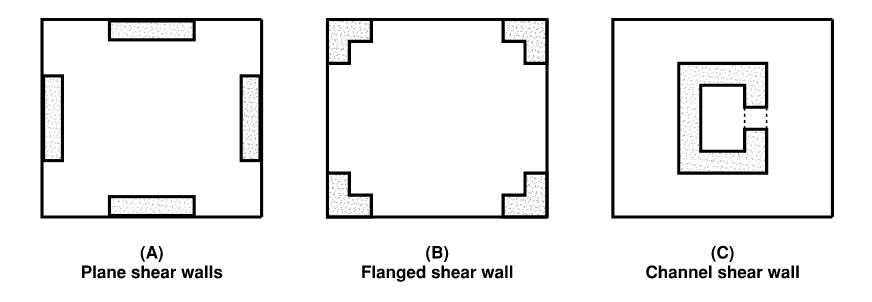

Shear walls are an effective solution to this problem. They are thick blocks of reinforced concrete that extend from a structure’s foundation to the top, adding stiffness and rigidity. Shear walls can be constructed in many shapes, as shown in Figure 2.

Of course, there are other arrangements of shear walls, and the design engineer must select one that suits the project at hand.

In structures, the greatest shear force occurs at the supports or at locations of concentrated loads therefore extra care and provisions are provided at these critical locations to improve structural integrity. Shear walls are solid masses that will typically run across multiple floors in a structure, thus it’s essential to coordinate with other services and architecture when proposing and designing shear walls.

Design procedure

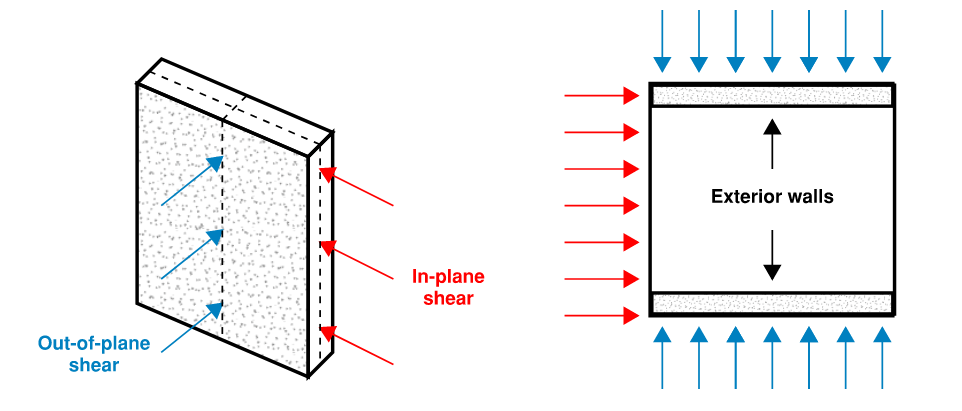

This design guide follows AS 3600 Section 11 [1], which provides directions on designing braced walls subject to in-plane loads only and a combination of both in-plane and out-of-plane loads. It’s important to distinguish the differences between in-plane and out-of-plane actions, as AS 3600 sets out distinctively different procedures for them.

In-plane loads act along the axis of a surface and out-of-plane loads act perpendicular to the surface. Figure 3 illustrates in-plane and out-of-plane shear caused by respective load actions on a wall. Typically, only the walls in the exterior perimeter experience both in- and out-of-plane loads, whereas interior walls experience just in-plane loads.

AS 3600 Section 11 applies to braced planar walls (i.e. not curved or tapered), which are defined as walls that “form part of a structure that does not rely on the out-of-plane strength and stiffness of the wall”, and the connection of the wall to the rest of the structure can transmit:

- Any calculated load effects

- 2.5% of the total vertical load the wall is designed to carry, but not less than 2kN per metre length of the wall

If the wall is braced, and is only subject to in-plane load effects (i.e. in-plane shear and bending), then the wall is designed in accordance with Clauses 11.2 ~ 11.7. However, if the wall is subject to both in- and out-of-plane load effects (i.e. there is additional out-of-plane shear and bending) then the wall must be designed as a slab or a column.

The wall may be designed as a slab using AS 3600 Section 9 if the stress at the mid-height of the wall due to design in-plane bending and axial forces is less than 3% of the concrete characteristic strength. In doing so, deflections due to in-plane loads and long-term effects (e.g. creep, shrinkage) must be considered in the calculation of bending moments and ensure that the ratio of effective height and thickness is less than 50. Effective height is covered in the following sections. Otherwise, the wall may be designed as a column using AS 3600 Section 10 but its slenderness and in-plane shear must be determined using Section 11. The out-of-plane shear should be checked in accordance with Section 8.

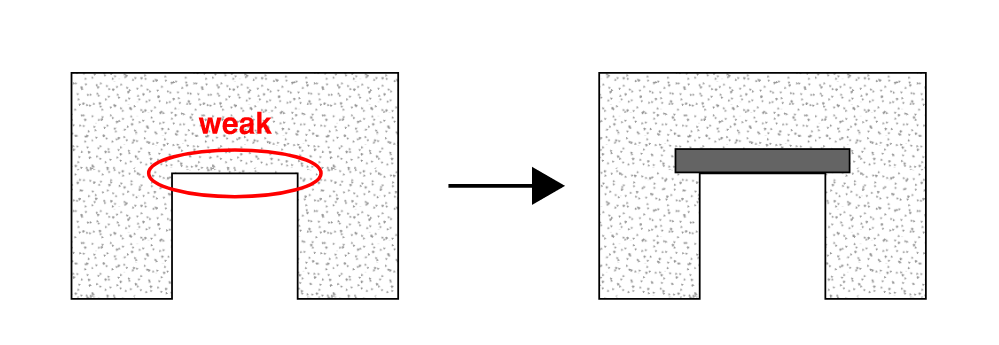

Often, openings are required in shear walls for human access (e.g. elevator shafts), windows or doorways, as seen in Figure 4. In these situations, the areas straight above the opening are significantly weaker than others. To counteract these internal stresses, ‘lintels’ are placed to act as beams to support additional height.

\( \textbf{1}\space\)Shear Wall - In-Plane Loads Only

Step 1. Determine the effective height

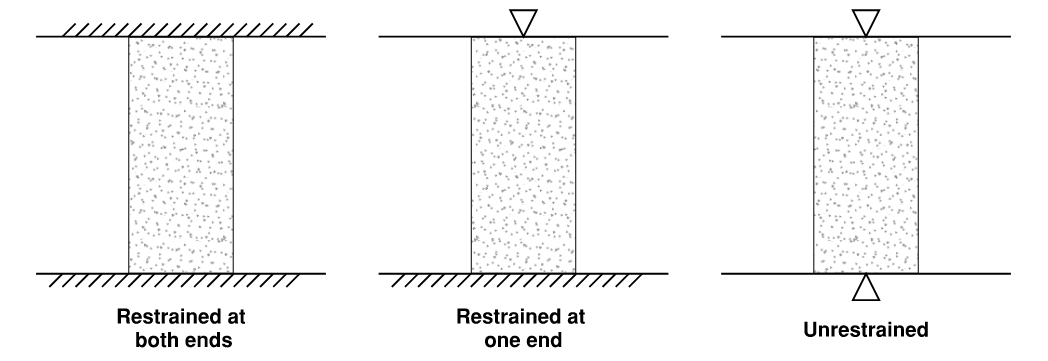

AS 3600 Section 11.4 defines the effective height factor k, which takes into account the buckling of the wall and the restraint condition. For a wall with horizontal length \(L_1\) and floor-to-floor height of \(H_w\), the effective height \(H_{we}\)=\(kH_w\). The effective height represents the proportion of the wall that is considered to behave as load-resisting.

For walls in one-way buckling with floors providing lateral supports at both ends:

- k = 0.75 if the wall is restrained against rotation at both ends

- k = 1.0 If the wall is restrained against rotation at no or only one end

For walls in two-way buckling with floors and intersecting walls providing lateral supports at three sides:

$$k=[11+(Hw3L1)2]>0.3k = \left[\frac{1}{1 + \left(\frac{H_w}{3L_1}\right)^{2}}\right] > 0.3 k=[1+(3L1Hw)21]>0.3$$

For walls in two-way buckling with floors and intersecting walls providing lateral supports at four sides:

$$k=L12Hwif Hw>L1k = \frac{L_1}{2H_w} \quad \text{if } \(H_w\) > \(L_1\)$$

$$k=2HwL1if Hw>L1$$

Step 2. Determine the design axial strength

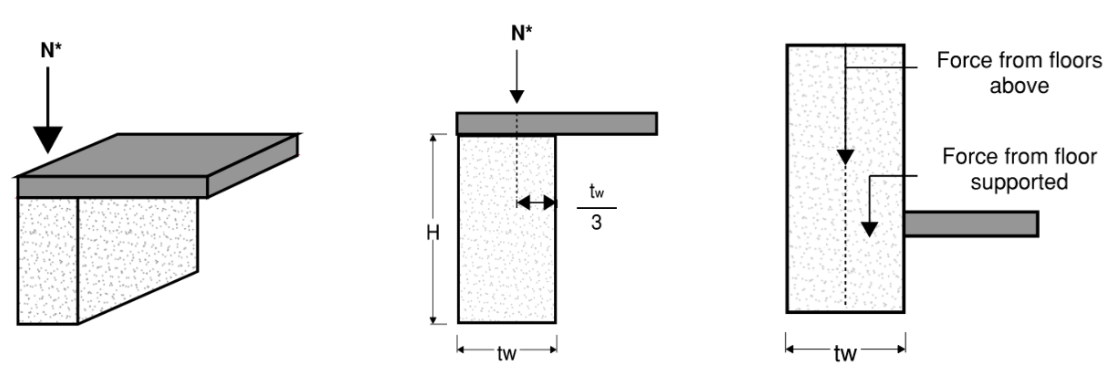

AS 3600 Section 11.5 outlines the method for designing the axial strength of walls subject to vertical forces, which cause in-plane bending of the wall. The wall is treated as a combination of segments, and each segment is designed for the highest stress occurring in that segment.

There are some limitations on the method used in this section, as provided in Clause 11.5.3:

- The design axial stress in the member must be less than 3 MPa, unless vertical and horizontal reinforcements are provided on both wall faces such that the stress is divided equally between them

- Ratio of effective height \(H_{ew}\) and thickness \(t_w\) of the wall must be less than 20 if singly reinforced and less than 30 if doubly reinforced (i.e. if there are more reinforcements, the wall may be taller

- The wall cannot be constructed on soils with soil classification \(D_c\) or \(E_e\), as defined in AS 1170.4, and in a building which may be subject to seismic loads

If the wall does not satisfy all of the conditions above, then it must be designed as a column. If it does, then it may be designed as a wall, with design axial strength taken as:

$$ϕ Nu=ϕ(tw−1.2e−2ea)0.6fc′>N∗$$

- \(Φ\) = 0.65

- \(t_w\) = thickness of the wall

- e = eccentricity of the applied load measured perpendicular to the plane of the wall

- \(e_a\) = additional eccentricity

$$e_a=\frac{(H_{we})^2}{2500t_w}$$

- f'_c = characteristic strength of concrete

The eccentricity e depends on various factors:

e is taken as one third of the depth of the bearing area as shown in Figure 5, if the floor is discontinuous

e is zero if the floor is cast in situ and continuous over the wall

e of aggregated load from all floors above is zero

The resultant eccentricities of the load from floors above and the floor supported on top of the wall in design must be no less than 0.05\(t_w\).

Step 3. Determine the critical section for shear

All sections of a wall must be designed to withstand the most critical shear force acting on the wall. The location of the this critical shear is taken as the minimum of the shear at a distance 0.5\(L_w\) or 0.5\(H\) from the base of the wall, where L_w and H the length and effective height of the wall, respectively.

Step 4. Determine the concrete contribution to shear strength

The ultimate wall shear strength excluding reinforcements (i.e. just concrete) is taken as:

$$V_{uc} = \left(0.66\sqrt{f'_c} - 0.21\frac{H}{L_w}\sqrt{f'_c}\right) \cdot 0.8L_wt_w \quad \text{if } \frac{H}{L_w} \leq 1$$

$$V_{uc} = \left[0.05\sqrt{f'_c} + \frac{0.1\sqrt{f'_c}}{\left(\frac{H}{L_w}-1\right)}\right] \cdot 0.8L_wt_w \quad \text{if } \frac{H}{L_w} > 1$$

Where:

$$V_{uc}>0.17\sqrt{f'_c}\left(0.8L_wt_w\right)$$

Step 5. Determine the steel reinforcement contribution to shear strength

The contribution of reinforcement in a wall to its ultimate shear strength is taken as:

$$V_{us}=p_wf_{sy}\left(0.8L_wt_w\right)$$

Where:

- \(f_{sy}\) = yield strength of steel, no greater than 500 MPa

- \(p_w\) = reinforcement ratio, determined by:

a) For H/L_w ≤ 1:

- The lesser of the ratios of either the horizontal or vertical reinforcement area to the cross-sectional area of the wall.

b) For H/L_w > 1:

- Ratio of the horizontal reinforcement area to the cross-sectional area of the wall per meter in the vertical direction.

Step 6. Check the design shear strength of the wall

Once \(V_{uc}\) and \(V_{us}\) have been calculated, check the total shear strength of the wall against design action effects:

$$\phi\ V_u=\phi(V_{uc}+V_{us})>V^*$$

Where:

- \(Φ\) = capacity factor, determined in accordance with AS 3600 Table 2.2.2

Shear Wall - In- and Out-of-Plane Loads

Designing a Shear Wall as a Slab

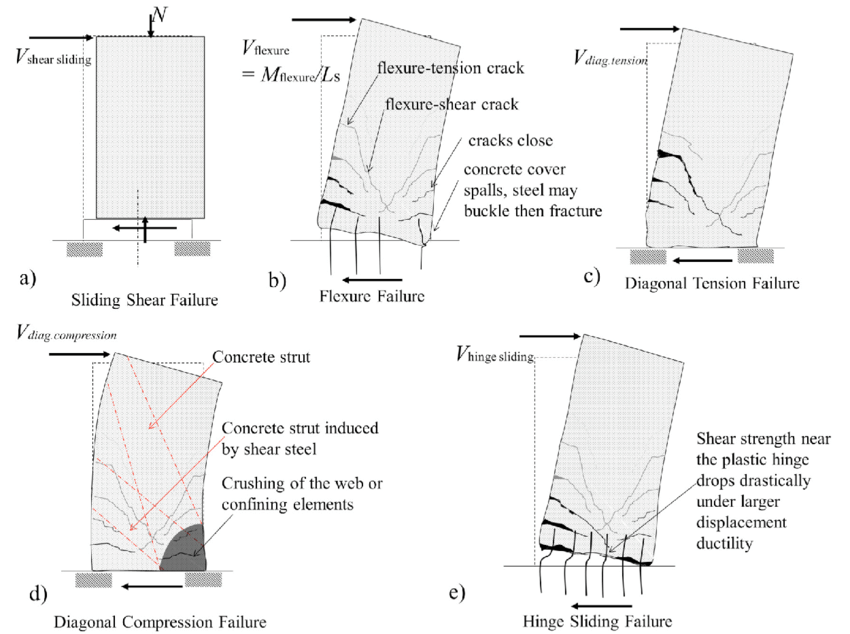

AS 3600 Section 9 provides directions on design checks for strength and serviceability of slabs. Unlike other structural components like columns and beams, slabs also need to consider the possibility of a punching shear failure, as well as flexural shear. Clause 9.3.2 states that where a shear failure can occur across the width of the wall (i.e. the flexural shear), the design strength of the slab shall be calculated in accordance with Clause 8.2 (as a beam). If shear failure can occur locally around a support or a concentrated load (i.e. punching shear), the engineer must follow Clause 9.3. Figure 7 illustrates some different failure modes for shear walls subject to axial and shear forces.

This design guide deals with the first case, where flexural shear occurs. Shear walls are unlikely to fail due to punching shear - such a scenario would mean that the beams connected to the wall are ‘ripped out’ by some external force.

$$V_{uc}=k_vb_vd_v\sqrt{f'_c}$$

Where:

\(k_v\) = shear factor

\(θ_v\) = (29 + 7000ε_x) the angle of inclination of the concrete compression strut to the longitudinal axis of the shear wall

\(b_v\) = effective web width for shear (equals the width of the wall for shear walls)

\(d_v\) = effective web depth for shear (equals the depth of the wall for shear walls)

\(f'_c\) = characteristic strength of concrete

AS 3600 Clause 8.2.4.3 - Simplified method for determining shear factor and the angle of strut inclination

The shear factor is dependent on the ratio of area of shear reinforcement to spacing. The standard offers two approaches for determining \(k_v\) and the angle of strut inclination \(θ_v\); a detailed method (Clause 8.2.4.2.2 ~ 3) and a simplified method (Clause 8.2.4.3). This design guide outlines the simplified method, but readers are encouraged to read the detailed method as well.

The simplified method is applicable to shear walls made of normal weight concrete with \(f'_c\) ≤ 65 MPa. In such cases, the following can be assumed:

$$\theta_v=36^\circ$$

$$k_v=\frac{200}{1000+1.3d_v}\leq0.15\quad\text{if}\;\frac{A_sv}{s}<\frac{A_{sv.min}}{s}$$

$$k_v=0.15\quad\text{if}\;\frac{A_{sv}}{s}\geq\frac{A_{sv.min}}{s}$$

AS 3600 Clause 8.2.4.4 - Secondary effects

If the stresses due to secondary effects such as creep, shrinkage and different temperature are more than 10% of the effects due to flexure and shear, they must be taken into account for the calculation of concrete shear strength

Step 2. Determine the steel reinforcement contribution to shear strength

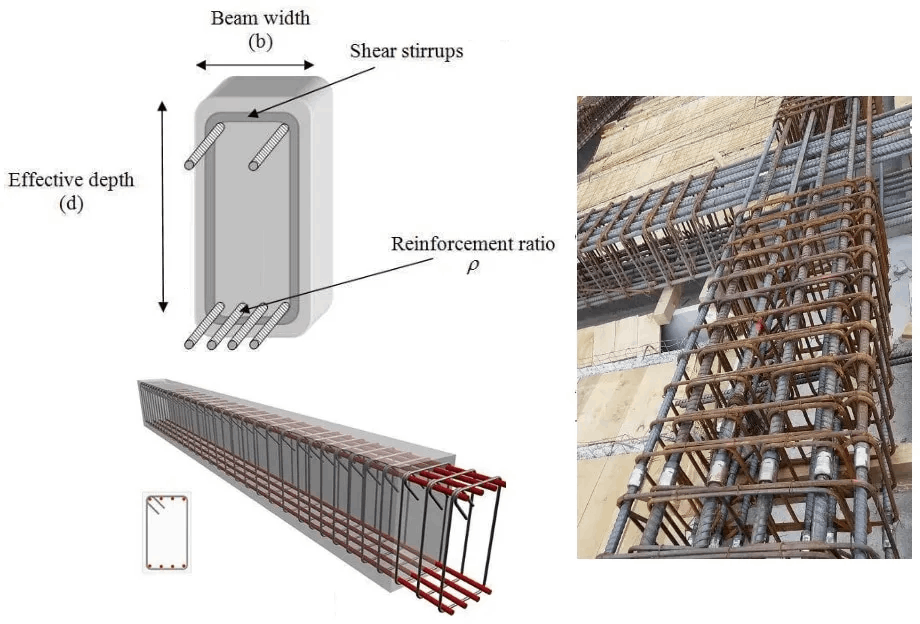

Shear reinforcement is similar to tensile and compressive reinforcement, except that its role in structures is to provide shear strength rather than axial strength. Additionally, shear reinforcement is often placed around the tensile and compressive rebars, providing not only shear strength but also confinement. This arrangement, as shown in Figure 8, helps the rebars stay in place and restraint movement.

AS 3600 Clause 8.2.5.2 - Transverse reinforcement for shear

The contribution of shear reinforcement to the overall shear wall strength can be calculated as:

- For perpendicular shear reinforcement:

$$V_{us}=\left(\frac{A_{sv}f_{sy.f}d_v}{s}\right)\cot{(\theta_v)}$$

- For inclined shear reinforcement:

$$V_{us}=\left(\frac{A_{sv}f_{sy.f}d_v}{s}\right)\left[\sin{(\alpha_v)}\cot{(\theta_v)}+\cos{(\alpha_v)}\right]$$

Step 3. Check the in- and out-of-plane design shear strength of the wall

Once \(V_{uc}\) and \(V_{us}\) have been calculated, check the total shear strength of the wall against design in-plane and out-of-plane shear forces:

$$\phi\ V_u=\phi(V_{uc}+V_{us})>V^*$$

Where:

- \(Φ\) = capacity factor, determined in accordance with AS 3600 Table 2.2.2

Designing a Shear Wall as a Column

If the ratio of the effective height to thickness exceeds 50 Clause 11.1 - (b)(i)(B) and is subject to out-of-plane shear forces, then it must be designed as a column in accordance with Section 10.

Step 1. Determine the effective height

The effective height of a shear wall when being designed as a column follows the same procedure as when it is being designed as a wall. Step 1 of the ‘In-plane loads only’ section should be followed where Clause 11.4 is used to determine k rather than Clause 10.5.3.

Step 2. Determine the buckling load

AS 3600 Clause 10.4.4 - Buckling load

The buckling load Nc can be calculated as:

$$N_c = \left(\frac{\pi^2}{L_e^2}\right)\left[182d_o\frac{(\phi M_c)}{(1+\beta_d)}\right]$$

Where:

\(L_e\) = \(kH_w\) = Effective Height of the wall

\(M_c\) = particular ultimate strength in bending (\(M_c\) = \(M_{ub}\) with \(k_u\) = 0.545 and \(φ\) = 0.65)

\(d_o\)= Distance from the compressive fibre of the wall to the centroid of its tensile reinforcement

\(β_d\) = G/(G+Q) where G and Q are design axial load component due to permanent dead and live actions, respectively

Step 3. Determine the moment magnifier for a braced column

The moment magnifier accounts for additional bending moments that occur due to slenderness effects. The largest bending moment that occurs along the wall due to design actions is multiplied by the moment magnifier, and the resultant moment is used for calculations instead. The magnifier can be calculated as:

$$\delta_b=\frac{k_m}{1-\frac{N^*}{N_c}}\geq1\quad\text{(Cl.\,10.4.2)}$$

$$k_m=0.6-0.4\frac{M_1^*}{M_2^*}$$

Where \(M*_1\) and \(M*_2\) are the design bending moments at the ends of the column.

- If \(M*_2\) is less than or equal to 0.05 ⋅ thickness of the wall ⋅ design axial load, then the ratio of \(M*_1\) and \(M*_2\) should be taken as 1.0

Step 4. Determine the slenderness

The slenderness of a shear wall is expressed as:

$$\(\frac{L_e}{r}<120\quad\text{(Cl\ 10.5.1)}\)$$

Where

- \(r\) = the radius of gyration and determined by r=0.3D for rectangular cross-sections.

- \(L_e\) = \(kH_w\) = Effective Height of the wall

Step 5: Design for Axial Strength

AS 3600 Clause 10.2.1 provides two options for the design of columns, one as a short column and the other as a slender column

The slenderness determines whether a shear wall is to be designed as a short column or a slender column. A short column fulfils the following criteria:

$$\frac{L_e}{r}\leq\ max\left(25,\alpha_c\left(38-\frac{f'_c}{15}\right)\left(1+\frac{M_1^*}{M_2^*}\right)\right)$$

Where:

$$\alpha_c=\sqrt{2.25-\frac{2.5N^*}{\phi\,N_{uo}}}\quad\text{for}\;\frac{N^*}{\phi\,N_{uo}}\geq15$$

$$\alpha_c=\sqrt{\frac{1}{\frac{3.5}{\phi\,N_{uo}}}}\quad\text{for}\;\frac{N^*}{\phi\,N_{uo}}<15$$

If the slenderness of the wall does not meet the criteria, it shall be designed as a slender wall.

Step 5.1 - Short column

Short columns are designed with accordance with AS 3600 Clauses 10.3, 10.6 and 10.7.

The governing axial strength is taken as the ultimate strength in compression before bending, the squash load \(V_{uo}\). The assumptions made are in Clause 10.6.2.2.

The axial capacity for the nominated column can be determined by:

$$\phi\,N_{uo}=\phi\left(\alpha_1f'_cA_c+A_sf_{sy}\right)$$

Where:

$$\alpha_1=1.0-0.003f'_c$$

- Within the limits of 0.72 ≤ \(α\) ≤ 0.85

- \(Φ\) = capacity factor, determined in accordance with AS 3600 Table 2.2.2

Strength in bending can be determined separately about each principal axis or by AS 3600 Clause 10.6.4:

$$\left(\frac{M_x^*}{\phi\,M_{ux}}\right)^{\alpha_n}+\left(\frac{M_y^*}{\phi\,M_{uy}}\right)^{\alpha_n}\leq1.0$$

- \(M_{ux}\), \(M_{uy}\) = Strength in bending about the x and y axes, calculated separately

- \(M*_x\), \(M*_y\) = Design in bending about the x and y axes

$$\alpha_n=0.7+1.7\frac{N^*}{\phi\,N_{uo}}\quad\text{where}\;1\leq\alpha_n\leq2$$

Step 5.2 - Slender column

Slender columns are designed according to AS 3600 Clauses 10.4, 10.5 and 10.6.

When designing a slender column to bending, the design moment is to be multiplied by a moment magnifier δ (calculated in step 3) due to slenderness effects.

The buckling load \(N_c\) can be calculated from Clause 10.4.4

$$N_c=\left(\frac{\pi^2}{L_e^2}\right)\left[182d_o\frac{\phi\,M_c}{1+\beta_d}\right]$$

Where:

- \(M_c\) = \(M_{ub}\) (\(k_u\) = 0.545 and \(φ\) =0.65)

Step 6: Design for shear

A shear wall designed as a column will be under both in-plane and out-of-plane shear. Design for in-plane shear is subject to the requirements of AS3600 Clause 11.6 and out-of-plane shear is checked under AS3600 Section 8.

In-plane shear

The design strength of a shear wall subject to in-plane shear forces is expressed as \(φV_u\)

Where:

$$V_u<V_{u,max}=0.2f'_c(0.8L_wt_w)$$

and

$$V_u=V_{uc}+V_{us}$$

The modification factor \(φ\) is determined using AS3600 Table 2.2.2 The contribution of shear strength by concrete \(V_{uc}\) is calculated by:

- For \(H_w\)/\(L_w\) ≤ 1,

$$V_{uc}=\left(0.66\sqrt{f'_c}-0.21\frac{H_w}{L_w}\sqrt{f'_c}\,0.8\right)L_wt_w\quad\text{(Cl\,11.6.3(1))}$$

- For \(H_w\)/\(L_w\) > 1,

$$V_{uc} = \min \left( \left[0.66\sqrt{f'_c} - 0.21\frac{H_w}{L_w}\sqrt{f'_c}\right]0.8L_wt_w, \left[0.05\sqrt{f'_c} + \frac{0.1\sqrt{f'_c}}{\frac{H}{L_w}-1}\right]0.8L_wt_w \right)\quad\text{(Cl\,11.6.3(2))}$$

Where:

$$V_{uc}\geq0.17\sqrt{f'_c}\left(0.8L_wt_w\right)$$

The contribution of shear strength by steel reingorcement \(V_{uc}\) is calculated by:

$$V_{us}=p_wf_{sy}(0.8L_wt_w)\quad\text(Cl\,11.6.4)$$

Where \(p_w\) is determine by:

- For \(H_w\)/\(L_w\) ≤ 1,

The lesser ratio of horizontal or vertical reinforcement area to the cross-sectional area of wall per square metre

- For \(H_w\)/\(L_w\) > 1

Ratio of horizontal reinforcement area to the cross-sectional area of wall per square metre

Out-of-plane shear

Out-of-plane shear for a shear wall designed as a column follows the provisions laid out in AS 3600 Clause 8.2. This procedure is identical to the shear design of a wall as a slab, as outlined in the previous section.

Step 7: Determine reinforcement properties

Reinforcement design for shear walls as columns follow AS 3600 Clause 10.7 and 11.7 which outlines requirements for columns and shear walls respectively.

From Clause 10.7.1, the cross-sectional area of longitudinal reinforcement is taken as:

$$0.01A_g\leq\,A_{sc}\,\leq0.4A_g$$

Except for cases such that:

$$A_{sc}f_{sy}>0.15N^*$$

- and the column area is larger than required

- The placement of reinforcement hinders the forming of concrete at splices and joints.

Once the shear design is complete the appropriate stirrups and spacing can be selected. From Clause 8.3.2.2 shear reinforcement shall be placed longitudinally. Where the maximum spacing determined by:

$$min(0.5D,\,300mm)\$$

or

$$min(0.75D,\,500mm)\quad\text{for}\;V^*\leq\phi\,V_{u.min}$$

The maximum transverse spacing across the width of the member is determined by:

$$min(D,\,600mm)$$

References

[1] Standards Australia, AS 3600 Concrete Structures, Sydney, Australia, 2018

[2] T. O. Tang and R. K.L. Su, “Shear and Flexural Stiffnesses of Reinforced Concrete Shear Walls Subjected to Cyclic Loading,” The Open Construction and Building Technology Journal, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 104–121, Jul. 2014,